CHEFSAYS

Chef Says: Jiaozi = dumplings

11/13/2015

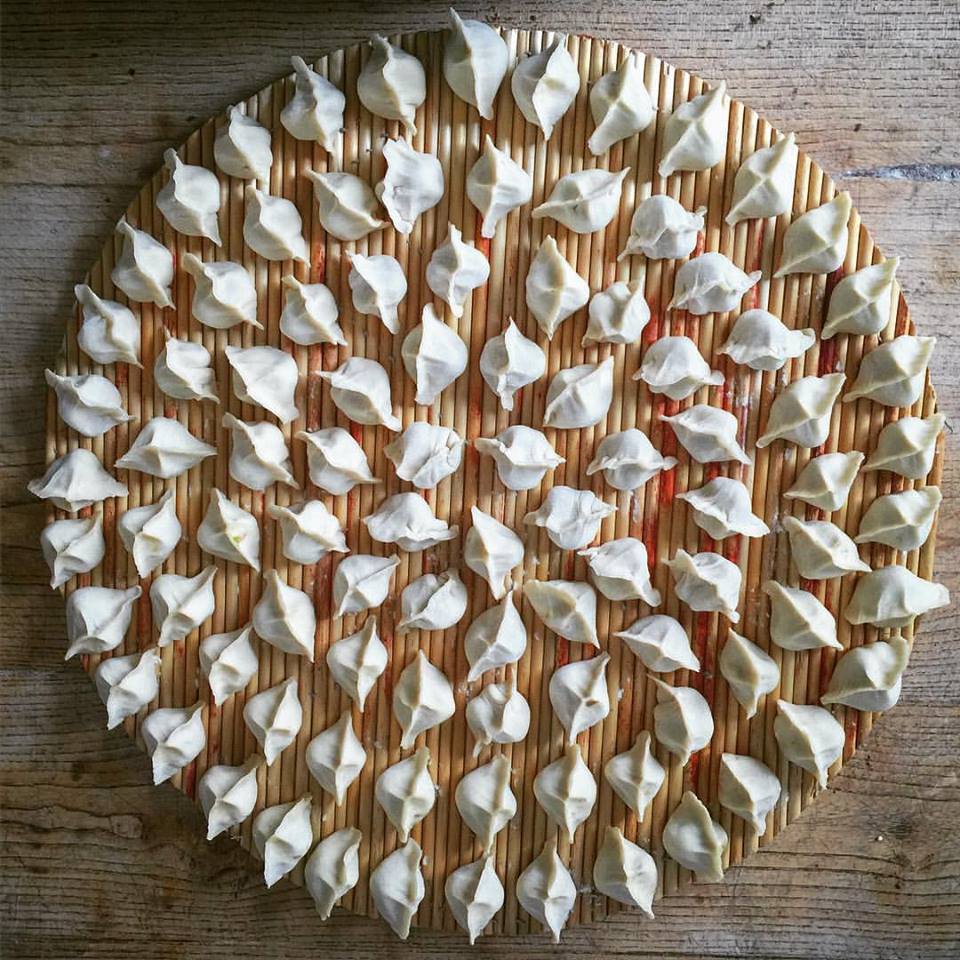

In this issue of Chef Says, our friend and former sushi chef Daniel Lu (@tastyfoodwithdaniellu) teaches us how to make one of the most common staple Chinese dishes there is: jiaozi.

(photo: https://instagram.com/p/9KkVr2JDc9/)

(photo: https://instagram.com/p/9KkVr2JDc9/)

The dish itself is a Chinese type of dumpling in which ground meat (generally pork) mixed with some sort of vegetable filling is wrapped inside thinly rolled dough. There are many variations and similar items to the jiaozi including: 1) baozi (包子), which has bun based wrappers (airy, yeast-based dough wrappers) that are steamed; 2) wonton/huntun (馄饨), which is generally made of a wheat flour dough and has a thinner wrapper than the traditional jiaozi; and 3) Goutie (锅贴), which is simply a pan-fried version of jiaozi.

To summarize:

For a more comprehensive list, check out this informative guide on lucky peach!

Jiaozi can also be found in many other Asian cultures. For example, pan-fried jiaozi (or guotie) has been adapted to Japanese cuisine in the form of the gyoza (ギョーザ, ギョウザ). These differ from their Chinese counterparts through a richer garlic flavor and thinner dumpling wrappers. In Korean cuisine, dumplings (known as mandu) are served in either: 1) grilled/fried variations known as gunmandu (군만두), 2) steamed variations known as jjinmandu (찐만두), or 3) boiled variations known as mulmandu (물만두). In western cuisine, dumplings are found in the form of ravioli (Italian), pelmeni (Russian), and many more.

Traditionally, the Chinese families stick to a certain combination of ingredients to form the more "classic" flavors. Such combinations include: chives and pork, cabbage and pork, zucchini and eggs, and chives and eggs. The ground pork is often also substituted with diced shrimp. There has also been numerous classic flavors made with wild vegetables and fungus, such as purslane, shepherd's purse, wooden ear mushrooms, etc. In future issues of #LEARNABOUT and Chef Says, we will introduce more wild vegetables to you.

Salt: Self-explanatory.

Salt: Self-explanatory.

Soy Sauce: Many different types of soy sauce exist out there. Japanese soy sauce and Chinese soy sauce also have variations among them that can impact the flavor profile we’re looking for with the dumplings. Perhaps the biggest variation among the different types of soy sauce is light vs dark soy sauce. As the name suggests, dark soy sauce is darker in color and tends to be more viscous, but is often lighter in saltiness. Light soy sauce is the most common type of soy sauce; however, and it is what we’ll be using today for this article.

Vegetable Oil: Any oil will do.

Sesame Oil: This is an optional ingredient (adds a complex sesame flavor), but we highly highly recommend adding it.

Alcohol: Any kind of colorless cooking wine will do (generally Chinese Shaoxing cooking wine is used), but today we’ll be using sake (Japanese rice wine) in its place.

Now let’s make the dough/wrappers! Of course you can purchase pre-made dumpling wrappers (if you do, make sure you get the round wrappers and not the square wonton wrappers), but what’s the fun in that? Making the dough is very simple and only requires two ingredients: flour and hot/boiling water.

All-Purpose Flour: (2 cups) Flour is the base for most dough out there (both western and eastern cuisines). This recipe makes enough dough to use up roughly ⅓ of the pork/cabbage filling, so feel free to scale this up or down to suit your needs!

All-Purpose Flour: (2 cups) Flour is the base for most dough out there (both western and eastern cuisines). This recipe makes enough dough to use up roughly ⅓ of the pork/cabbage filling, so feel free to scale this up or down to suit your needs!

Near-Boiling Water: (¾ cups) One of the biggest differentiators of eastern style dough is the usage of hot water. Hot water dough behaves drastically different from cold water/western doughs. Adding hot, near-boiling water to the dough denatures many of the proteins found inside of the flour, and results in a significantly decreased amount of gluten found in the dough. Hot water dough are not nearly as elastic or springy as western dough (such as pizza dough).

To make the jiaozi wrappers:

As the dough is sitting and resting, we’re going to make the pork/cabbage filling. First, cut up the cabbage to the smallest chunks that you can.

If your dough is too sticky when you’re rolling it out, feel free to add more flour to your working surface and/or hands!

After you’ve rolled out your dough, we’re going to cut the dough into small pieces. Start by cutting the dough cylinder into ½ to 1-inch pieces. While you’re cutting the dough, it helps to rotate the dough cylinder a quarter turn after each cut.

Once your dough pieces are cut, flatten them out with the palm of your hand to make small semi-flattened circles.

Roll each of your small circular dough pieces out to a larger, flatter circular wrapper. We made ours out to be roughly a 3 ½ inch to 4-inch diameter. Very importantly: make sure that you leave the center of the wrapper to be thicker than the edges, because when you fold the dumplings, the center will stretch, and if you leave it too thin, the dumplings will explode when you boil them.

Now that both your wrappers and your filling is made up, lets have some fun and wrap everything together!

Start by taking one of your jiaozi wrappers and place it in your hand. Add a small amount of filling (only add enough filling to the point where you’re confident that you can create a complete seal. If this is your first time making jiaozi, start with a small amount of filling - size of a quarter or so).

To fold the wrapper around your filling and create the classic horn shaped jiaozi:

Step 1: Place filling on the wrapper. Again, only use as much filling as you’re comfortable with.

Step 1: Place filling on the wrapper. Again, only use as much filling as you’re comfortable with.

Step 2: Take the bottom of the wrapper and pinch it up to the top of the wrapper. Be sure that no filling is oozing out of the sides.

Step 2: Take the bottom of the wrapper and pinch it up to the top of the wrapper. Be sure that no filling is oozing out of the sides.

Step 5: Follow through with Step 4. You should have one side completely sealed up after Step 5.

Step 6: Do the other side, press the opening to form 2 flaps just like Step 3.

Step 6: From a different angle.

Step 7: Do the same as Step 3.

Step 8: Do the same as Step 4 and follow through.

After all these steps, you will have a perfectly shaped jiaozi!

Its most important that all of the filling is sealed in. It doesn’t matter if the dumpling looks ugly or not! It’ll taste great either way :)

Now that you’ve made one of these jiaozi, let’s continue by making lots of them!

Once all of your wrappers and/or filling has been used up, you have two options. Freeze them down in a freezer ziploc bag (they’ll last a few months in the freezer this way), or cook them and eat them now! The classic way to cook these dumpling is by using a boiling method. You could of course make guotie (potstickers) as well if you’d like, but we’re going to be traditional today and show you the boiling process.

Step 1: Bring water to a boil in a large sauce pot on high heat.

Step 1: Bring water to a boil in a large sauce pot on high heat.

Step 2: Once the water is boiling, add enough jiaozi to the pot (make sure you only add enough to cover the bottom of the pot--you don't want to add too much jiaozi at once).

Step 3: Cover the pot and wait until the water comes back up to a boil.

Step 4: Once the jiaozi/water has reached a boil, add a cup of cold water to the pot, stir with a wooden spoon, and then cover the pot and wait until it reaches a boil again.

Step 5: Repeat the process outlined in step 4 two more times.

Throughout the whole process, it's good to keep stirring the pot with a wooden spoon, especially when you first put the dumplings into the boiling water. This keeps the dumplings from sticking to each other.

A good check to see whether the dumplings are fully cooked or not is to look at whether the dumplings are floating in the water or not. Uncooked dumplings will always sink to the bottom of the pot, whereas cooked dumplings will float. This process happens due to a change in the density of the dumplings as it is being cooked.

Once the dumplings are cooked, strain them out of the boiling liquid and onto a plate. We used a soup skimmer spoon to do this (it works amazingly well).

Now, as far as a dipping sauce goes for the dumplings, many different regions across China will use different things. Here, let's focus on one that involves three simple ingredients (two of which we’ve already used to make the jiaozi filling).

Chengkiang/Zhenjiang Vinegar: THE ingredient used traditionally in jiaozi dipping sauces.

Chengkiang/Zhenjiang Vinegar: THE ingredient used traditionally in jiaozi dipping sauces.

Sesame Oil

Soy Sauce (Light)

Mix these ingredients at a 8:1:1 ratio to complete your dipping sauce! Your jiaozi are ready to eat :)

Optional Bonus

Dumplings, Buns, Wontons…..What’s the difference!?

Jiaozi (饺子) was thought to have been invented sometime during the Eastern Han dynasty (around 220 AD), but its origins may even trace further back to the Zhou dynasty (1,056-256 BCE) where a penned recipe for something similar to jiaozi was first discovered.The dish itself is a Chinese type of dumpling in which ground meat (generally pork) mixed with some sort of vegetable filling is wrapped inside thinly rolled dough. There are many variations and similar items to the jiaozi including: 1) baozi (包子), which has bun based wrappers (airy, yeast-based dough wrappers) that are steamed; 2) wonton/huntun (馄饨), which is generally made of a wheat flour dough and has a thinner wrapper than the traditional jiaozi; and 3) Goutie (锅贴), which is simply a pan-fried version of jiaozi.

To summarize:

Pinyin

|

English Name

|

Chinese Name

|

Yeast in Dough?

|

Cooking Method

|

Jiaozi

|

dumplings

|

饺子

|

no

|

boil

|

Guotie

|

pan-fried dumplings

|

锅贴

|

no

|

pan-fry

|

Baozi

|

buns

|

包子

|

yes

|

steam

|

Hundun

|

wontons

|

馄饨

|

no

|

boil

|

For a more comprehensive list, check out this informative guide on lucky peach!

Jiaozi can also be found in many other Asian cultures. For example, pan-fried jiaozi (or guotie) has been adapted to Japanese cuisine in the form of the gyoza (ギョーザ, ギョウザ). These differ from their Chinese counterparts through a richer garlic flavor and thinner dumpling wrappers. In Korean cuisine, dumplings (known as mandu) are served in either: 1) grilled/fried variations known as gunmandu (군만두), 2) steamed variations known as jjinmandu (찐만두), or 3) boiled variations known as mulmandu (물만두). In western cuisine, dumplings are found in the form of ravioli (Italian), pelmeni (Russian), and many more.

A Family Affair

During Chinese New Year (especially at midnight on Chinese New Year’s Eve), Jiaozi IS the food for families. One common tradition is for the entire family to gather around the kitchen and make the dumplings together.Traditionally, the Chinese families stick to a certain combination of ingredients to form the more "classic" flavors. Such combinations include: chives and pork, cabbage and pork, zucchini and eggs, and chives and eggs. The ground pork is often also substituted with diced shrimp. There has also been numerous classic flavors made with wild vegetables and fungus, such as purslane, shepherd's purse, wooden ear mushrooms, etc. In future issues of #LEARNABOUT and Chef Says, we will introduce more wild vegetables to you.

Step-by-Step Guide to Making Jiaozi

Now we’re going to show you how to make a classic flavor combination: the pork and cabbage jiaozi. To make these delicious dumplings, let's start out with the necessary ingredients for the pork/cabbage filling.

Cabbage: Napa (also known as Chinese Cabbage). You can generally find these in any major supermarket.

Ground Pork: 1 pound (usually enough for 6-8 people). Feel free to scale this amount down.

Ginger: One of the cornerstones of Chinese aromatics (along with scallions and garlic). Ginger itself is a rhizome, having a flavor profile that is sharp and intense while being light and floral at the same time. It is also great at cleansing strong odors from the other ingredients.

Scallions/Green Onions: Another cornerstone of Chinese aromatics. It’s rare that any savory Chinese dish to not use at least two of these three cornerstones. For our jiaozi today, we’ll be using scallions and ginger as our main aromatics.

Ground Pork: 1 pound (usually enough for 6-8 people). Feel free to scale this amount down.

Ginger: One of the cornerstones of Chinese aromatics (along with scallions and garlic). Ginger itself is a rhizome, having a flavor profile that is sharp and intense while being light and floral at the same time. It is also great at cleansing strong odors from the other ingredients.

Scallions/Green Onions: Another cornerstone of Chinese aromatics. It’s rare that any savory Chinese dish to not use at least two of these three cornerstones. For our jiaozi today, we’ll be using scallions and ginger as our main aromatics.

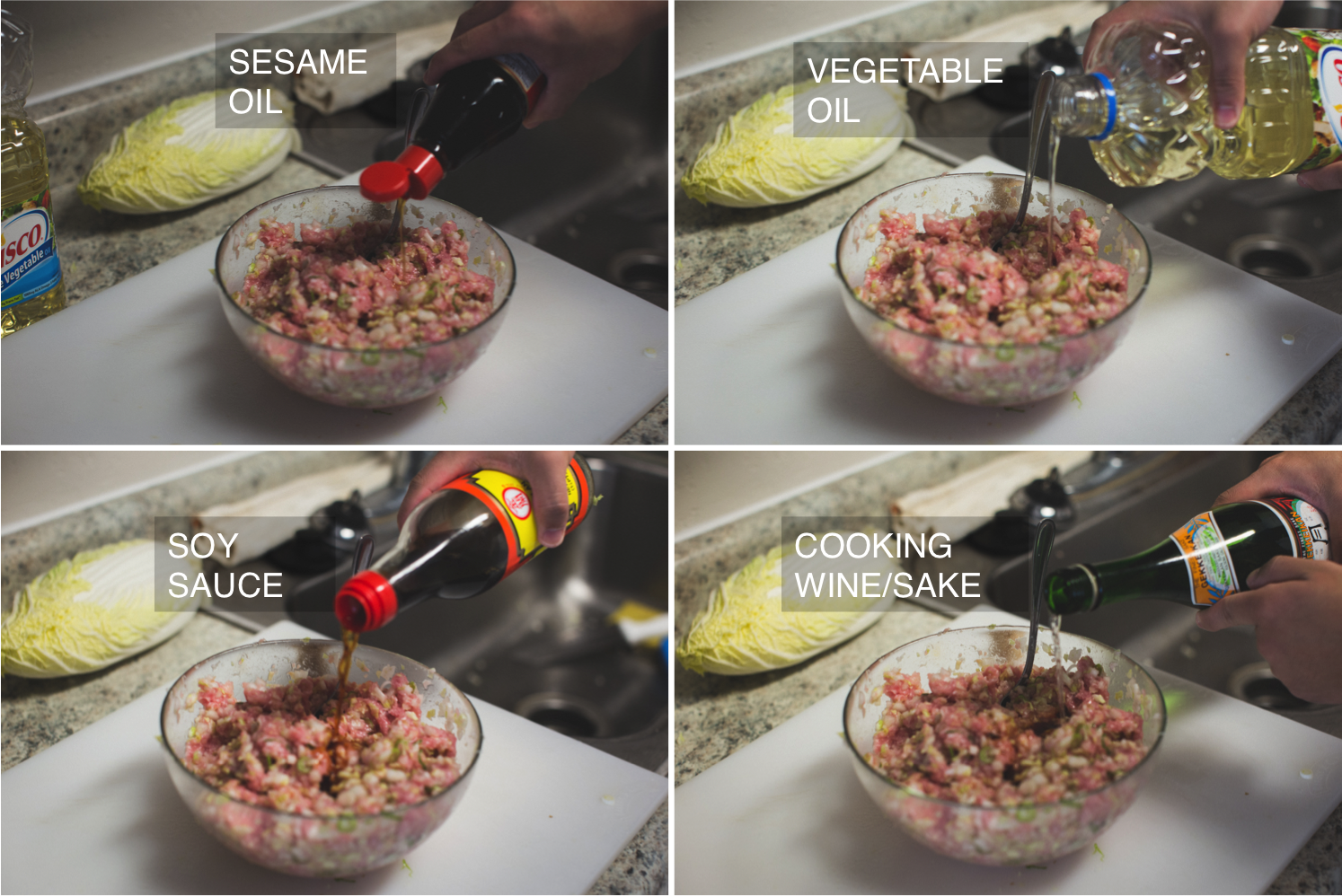

Soy Sauce: Many different types of soy sauce exist out there. Japanese soy sauce and Chinese soy sauce also have variations among them that can impact the flavor profile we’re looking for with the dumplings. Perhaps the biggest variation among the different types of soy sauce is light vs dark soy sauce. As the name suggests, dark soy sauce is darker in color and tends to be more viscous, but is often lighter in saltiness. Light soy sauce is the most common type of soy sauce; however, and it is what we’ll be using today for this article.

Vegetable Oil: Any oil will do.

Sesame Oil: This is an optional ingredient (adds a complex sesame flavor), but we highly highly recommend adding it.

Alcohol: Any kind of colorless cooking wine will do (generally Chinese Shaoxing cooking wine is used), but today we’ll be using sake (Japanese rice wine) in its place.

Now let’s make the dough/wrappers! Of course you can purchase pre-made dumpling wrappers (if you do, make sure you get the round wrappers and not the square wonton wrappers), but what’s the fun in that? Making the dough is very simple and only requires two ingredients: flour and hot/boiling water.

Near-Boiling Water: (¾ cups) One of the biggest differentiators of eastern style dough is the usage of hot water. Hot water dough behaves drastically different from cold water/western doughs. Adding hot, near-boiling water to the dough denatures many of the proteins found inside of the flour, and results in a significantly decreased amount of gluten found in the dough. Hot water dough are not nearly as elastic or springy as western dough (such as pizza dough).

To make the jiaozi wrappers:

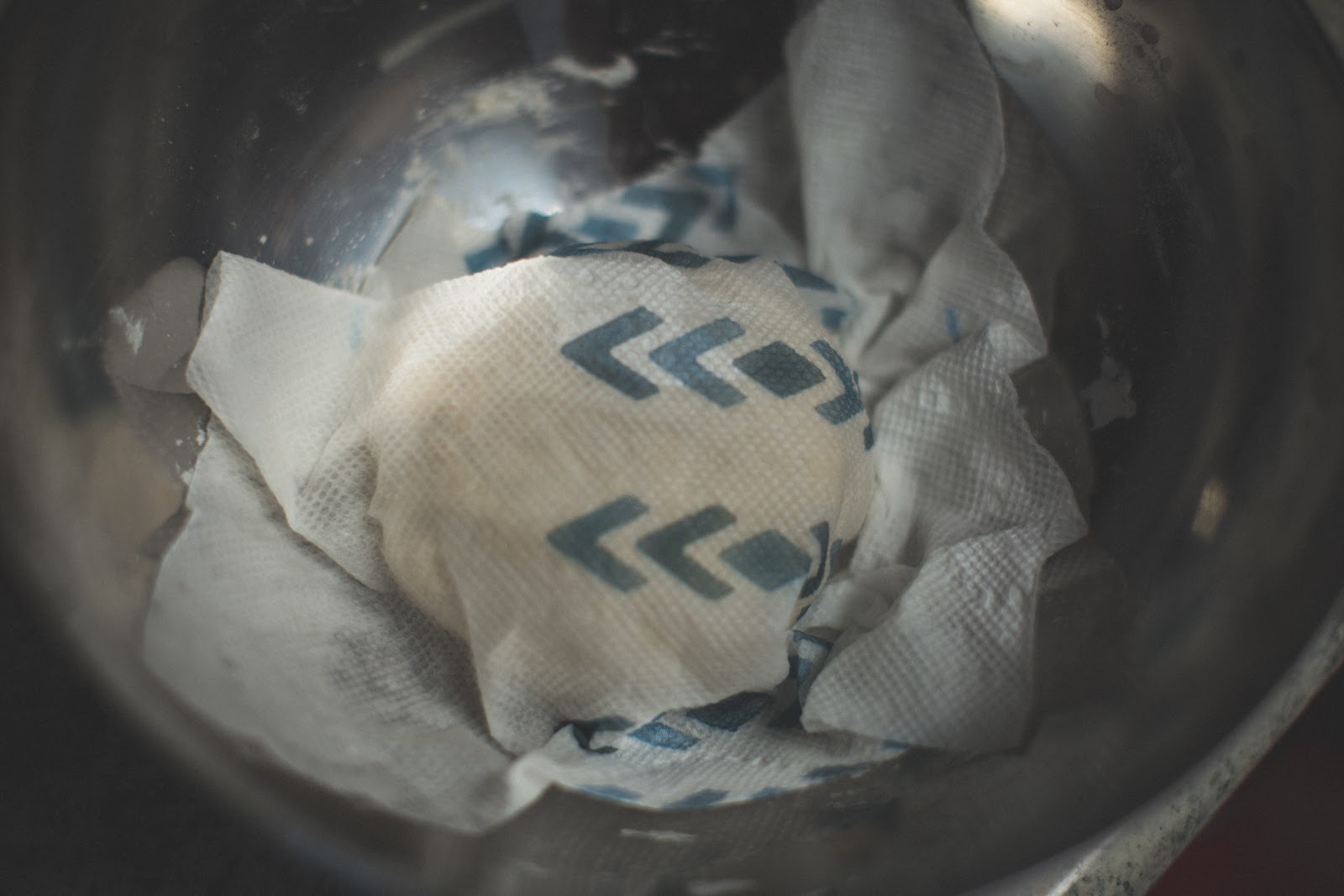

First add the hot/near-boiling water to the flour in a large mixing bowl.

Knead the dough until it comes together (roughly 2-5 minutes).

After the dough comes together, cover it with a damp cloth and let it rest for at least half an hour.

As the dough is sitting and resting, we’re going to make the pork/cabbage filling. First, cut up the cabbage to the smallest chunks that you can.

To cut the cabbage, Chinese cleavers work really well. Their large surface allows you to easily pick up and move the cabbage chunks into optimal positions for dicing. Note that the cabbage itself will release a lot of water. This is okay! Leave the water in, especially with the pork later. This allows you to have a wonderfully juicy dumpling filling in the end.

Add the diced up cabbage to your ground pork. In our case, we cut up roughly 7 large cabbage leaves and added it to roughly a pound of ground pork. Remember that the cabbage also is used as a contrasting textural element, so feel free to add more or less cabbage to your fillings.

Add salt (roughly a teaspoon and a teaspoon only -- we’re adding soy sauce later to help season the filling too), ginger, scallion and mix well. The added salt helps draw out a lot of the liquid from the cabbage leaves via a process known as osmosis. This helps greatly with keeping the filing moist and juicy.

For everything else, we’re going to be adding roughly half a tablespoon of the rest of the filling ingredients. The exception is soy sauce. Add roughly 2 tablespoons of that.

One thing that you may have noticed with Chinese cuisine is that everything is cut up into small chunks. Because many foods are stir fried, the small chunks result in a larger surface area, cooking the food faster. In the case of our jiaozi, the small diced up chunks allow for better mixing and more efficient seasoning of the filling.

After you’ve made your pork/cabbage filling and the dough has been resting for at least 30 minutes, we’re going to roll the dough into a long cylinder (roughly a 1 or 1 ½-inch diameter).

Add salt (roughly a teaspoon and a teaspoon only -- we’re adding soy sauce later to help season the filling too), ginger, scallion and mix well. The added salt helps draw out a lot of the liquid from the cabbage leaves via a process known as osmosis. This helps greatly with keeping the filing moist and juicy.

For everything else, we’re going to be adding roughly half a tablespoon of the rest of the filling ingredients. The exception is soy sauce. Add roughly 2 tablespoons of that.

One thing that you may have noticed with Chinese cuisine is that everything is cut up into small chunks. Because many foods are stir fried, the small chunks result in a larger surface area, cooking the food faster. In the case of our jiaozi, the small diced up chunks allow for better mixing and more efficient seasoning of the filling.

After you’ve made your pork/cabbage filling and the dough has been resting for at least 30 minutes, we’re going to roll the dough into a long cylinder (roughly a 1 or 1 ½-inch diameter).

First up, flour your working surface!

If your dough is too sticky when you’re rolling it out, feel free to add more flour to your working surface and/or hands!

Once your dough pieces are cut, flatten them out with the palm of your hand to make small semi-flattened circles.

Roll each of your small circular dough pieces out to a larger, flatter circular wrapper. We made ours out to be roughly a 3 ½ inch to 4-inch diameter. Very importantly: make sure that you leave the center of the wrapper to be thicker than the edges, because when you fold the dumplings, the center will stretch, and if you leave it too thin, the dumplings will explode when you boil them.

Start by taking one of your jiaozi wrappers and place it in your hand. Add a small amount of filling (only add enough filling to the point where you’re confident that you can create a complete seal. If this is your first time making jiaozi, start with a small amount of filling - size of a quarter or so).

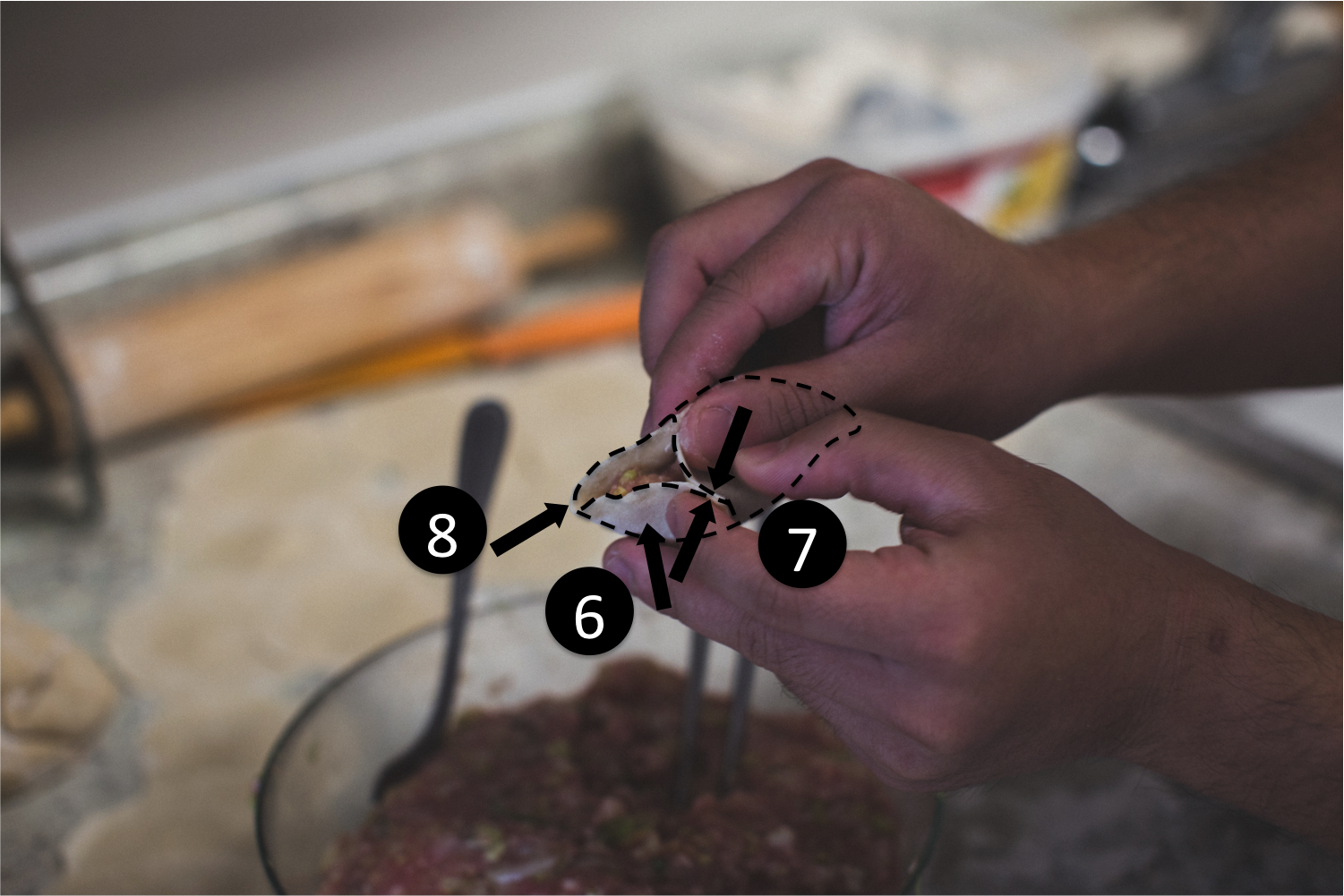

To fold the wrapper around your filling and create the classic horn shaped jiaozi:

Step 3: Form two flaps/loops on the side, and pinch the one closer to your hands.

Step 4: Press the other flap/loop inwards towards you.Step 5: Follow through with Step 4. You should have one side completely sealed up after Step 5.

Step 6: Do the other side, press the opening to form 2 flaps just like Step 3.

Step 6: From a different angle.

Step 7: Do the same as Step 3.

Step 8: Do the same as Step 4 and follow through.

After all these steps, you will have a perfectly shaped jiaozi!

Now that you’ve made one of these jiaozi, let’s continue by making lots of them!

Once all of your wrappers and/or filling has been used up, you have two options. Freeze them down in a freezer ziploc bag (they’ll last a few months in the freezer this way), or cook them and eat them now! The classic way to cook these dumpling is by using a boiling method. You could of course make guotie (potstickers) as well if you’d like, but we’re going to be traditional today and show you the boiling process.

Step 2: Once the water is boiling, add enough jiaozi to the pot (make sure you only add enough to cover the bottom of the pot--you don't want to add too much jiaozi at once).

Step 3: Cover the pot and wait until the water comes back up to a boil.

Step 4: Once the jiaozi/water has reached a boil, add a cup of cold water to the pot, stir with a wooden spoon, and then cover the pot and wait until it reaches a boil again.

Step 5: Repeat the process outlined in step 4 two more times.

Throughout the whole process, it's good to keep stirring the pot with a wooden spoon, especially when you first put the dumplings into the boiling water. This keeps the dumplings from sticking to each other.

A good check to see whether the dumplings are fully cooked or not is to look at whether the dumplings are floating in the water or not. Uncooked dumplings will always sink to the bottom of the pot, whereas cooked dumplings will float. This process happens due to a change in the density of the dumplings as it is being cooked.

Once the dumplings are cooked, strain them out of the boiling liquid and onto a plate. We used a soup skimmer spoon to do this (it works amazingly well).

Now, as far as a dipping sauce goes for the dumplings, many different regions across China will use different things. Here, let's focus on one that involves three simple ingredients (two of which we’ve already used to make the jiaozi filling).

Sesame Oil

Soy Sauce (Light)

Mix these ingredients at a 8:1:1 ratio to complete your dipping sauce! Your jiaozi are ready to eat :)

Optional Bonus

Though we are not sure why, a lot of Chinese will also drink the liquid that the jiaozi were boiled in. It's a hot, slightly thick, flour-y liquid that you add a bit of vinegar to and drink. Great for the soul I hear.

Daniel is currently a PhD student at the University of Minnesota studying the mechanics of blood flow in artificial blood vessels. His cooking roots stem all the way back to when he was a kid working in his parents' Japanese sushi restaurants in his hometown of Indianapolis, IN. Growing up around the restaurant meant that there was no way Daniel wouldn’t end up as a chef (in fact, he’s even made sushi for former Indianapolis Colts football players). Nowadays, Daniel likes to combine his scientific background with his cooking history to creative visually stunning and delicious dishes. You can follow him on Instagram @epicureaperture.

Chef Says

“Cooking and food in general is an amazing way to combine aspects of both science and art into a single dish (like jiaozi) that's both beautiful to look at and delicious to eat. Not only is cooking just like a complex science experiment, it is also a canvas for artists to paint and illustrate.”Daniel is currently a PhD student at the University of Minnesota studying the mechanics of blood flow in artificial blood vessels. His cooking roots stem all the way back to when he was a kid working in his parents' Japanese sushi restaurants in his hometown of Indianapolis, IN. Growing up around the restaurant meant that there was no way Daniel wouldn’t end up as a chef (in fact, he’s even made sushi for former Indianapolis Colts football players). Nowadays, Daniel likes to combine his scientific background with his cooking history to creative visually stunning and delicious dishes. You can follow him on Instagram @epicureaperture.

.jpg)

0 comments